An organization, seeking to foster a real conversation about our history of violent racism, lynching in particular, had the funding (from Google) to shoot me a compelling video ad on youtube that led me to explore their website. From their report:

When the era of racial terror and widespread lynching ended in the mid-twentieth century, it left behind a nation and an American South fundamentally altered by decades of systematic community-based violence against black Americans. The effects of the lynching era echoed through the latter half of the twentieth century. African Americans continued to face violent intimidation when they transgressed social boundaries or asserted their civil rights, and the criminal justice system continued to target people of color and victimize African Americans. These legacies have yet to be confronted.

The organization is called The Equal Justice Initiative. Their project is of crucial importance, in a country being made great again by people who deny our ongoing bloody history, and climate disruption, our 2500% higher rate of mass killing by gun than any other nation and many other horrors that are denied at our peril. The website is very well done. The historical section I read is clearly and beautifully written.

When I was in law school, twenty years ago, a case called U.S. v. Cruikshank was mentioned in a one sentence footnote in the casebook for Constitutional Law. As I began researching what happened to enforcement of the amendments intended to outlaw slavery, guarantee full citizenship to former slaves and give black men the right to vote, I stumbled on more details about the little known case. After reading the lower court decisions, and the Supreme Court’s final word, I came to understand that Cruikshank, as much as the aptly named Slaughterhouse cases (which gave a miserly reading of the rights of federal citizenship that would be our law for almost a century), was actually the death knell for the new rights of citizenship for black people in America.

When an organized, torch carrying crowd marched and chanted recently in Charlottesville, Virginia, protesting the proposed removal of a monument to the slaveholders’ armed rebellion against the U.S.A., the stink of an undiscussed history hung over that procession. There was the occasional shot of a screaming chap wearing a swastika, a chant about Jews, delivered by the marchers without love or irony, and also those carrying and wearing the symbols of those who enslaved and terrorized blacks. There was a near century, after the Civil War, of often public lynching that extended to twenty states, walking with these angry white men.

Most people, on many sides, many sides, have a revulsion for the symbols of racist regimes of the past, however little they might actually know about these notorious regimes. These symbols stand for a time when violent hatred ruled the day. That’s kind of the point of bringing these potent symbols to a rally. They are used to rub people’s faces in an easily recognizable worst case scenario for a minority, when the violent racists of the day ruled and the government smiled on the murderers.

Cruikshank was one of the leaders of a mob of angry whites, defeated Confederates, who swarmed into Colfax Louisiana on Easter Sunday 1873. They came heavily armed, on horseback, with at least one cannon. The whites were there to see that Negros did not get the final word on the vote, that no Negro take power over any white. They attacked the black Civil War veterans who were guarding the courthouse, defending the county seat of newly renamed Grant Parish after a bitterly contested election won, on black votes, by Republican advocates of black rights.

It was a slaughter, pure and simple. As many as fifty black men were killed hours after surrendering. The whites, who had overwhelming numbers, killed every black they came across, left their corpses rotting on the field on the day Jesus was resurrected and rose up to heaven. The failed federal prosecution of the perpetrators of what Eric Foner called the worst instance of racial violence of the Reconstruction era would, more than a century later, become a one sentence footnote in the Constitutional Law casebook. [1]

The federal prosecution over Cruikshank and his comrades was ruled unconstitutional by The Supreme Court. It said, amid pages of legal analysis that drily took the indictments apart point by point, that the Constitution protected former slaves only from government action– not from the actions of a private mob. It left enforcement of such crimes up to each individual state to deal with as they saw fit. The case quietly closed down all federal prosecution of outfits like the Ku Klux Klan.

The decision was a stinking piece of legalistic cavil, like other racially driven decisions over the years, but you can’t appeal that decision anywhere, of course, even if the Court is demonstrably sympathetic to the former enemies of the U.S. The ruling in Cruikshank led to all the defendants walking, triumphant as that iconic grinning Southern sheriff with his Red Man chewing tobacco pouch almost a century later, into a long period of unrestrained, often deadly, brutality against former slaves.

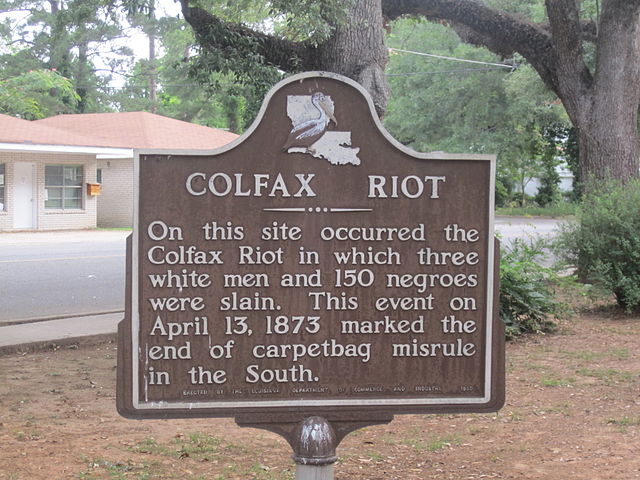

Here is a historical marker, put up by the state of Louisiana in 1950, photographed by Billy Hathorn (photo credit here).

At the end of the twentieth century only an enterprising law student with an overriding interest in history could find out anything more about the case, about the then largely unknown Colfax massacre, about any of this shit. As we march along in the twenty-first century, this is the kind of history we need to be learning from together. This website is an excellent tool for learning.

As the director of the Equal Justice Initiative writes:

We cannot heal the deep wounds inflicted during the era of racial terrorism until we tell the truth about it.

True dat, as my father would say.

[1] how’s this for a footnote?

Opposition among white Democrats to suffrage for blacks resulted in 1,081 political murders from April to November 1868. Almost all of the victims were black, and some of the whites who were killed were Republicans.