Apparently not part of all the news that’s fit to print in today’s online New York Times, on Saturday federal judge (and Trump-appointee) J. Nicholas Ranjan [1] finally threw out Trump 2020 and the RNC’s attempt to prevent expansion of voting in crucial swing state during a pandemic.

Judge Ranjan went into great detail explaining why each claim by Trump and the RNC had to fall, as a matter of law, on the merits, for lack of evidence. I see the Pennsylvania Attorney General’s office has already posted a PDF of the decision on its website. The judge began his 138 page decision (I’ve added paragraph breaks for easier reading):

After a careful review of the parties’ submissions and the extensive evidentiary record, the Court will enter judgment in favor of Defendants on all of Plaintiffs’ federal constitutional claims, decline to exercise supplemental jurisdiction over the state-constitutional claims, and dismiss this case.

This is so for two main reasons.

First, the Court concludes that Plaintiffs lack Article III standing to pursue their claims. Standing, of course, is a necessary requirement to cross the threshold into federal court. Federal courts adjudicate cases and controversies, where a plaintiff’s injury is concrete and particularized.

Here, however, Plaintiffs have not presented a concrete injury to warrant federal-court review.

All of Plaintiffs’ remaining claims have the same theory of injury—one of “vote dilution.” Plaintiffs fear that absent implementation of the security measures that they seek (guards by drop boxes, signature comparison of mail-in ballots, and poll watchers), there is a risk of voter fraud by other voters. If another person engages in voter fraud, Plaintiffs assert that their own lawfully cast vote will, by comparison, count for less, or be diluted.

The problem with this theory of harm is that it is speculative, and thus Plaintiffs’ injury is not “concrete”—a critical element to have standing in federal court.

While Plaintiffs may not need to prove actual voter fraud, they must at least prove that such fraud is “certainly impending.” They haven’t met that burden. At most, they have pieced together a sequence of uncertain assumptions:

(1) they assume potential fraudsters may attempt to commit election fraud through the use of drop boxes or forged ballots, or due to a potential shortage of poll watchers; (2) they assume the numerous election-security measures used by county election officials may not work; and (3) they assume their own security measures may have prevented that fraud.

All of these assumptions could end up being true, and these events could theoretically happen. But so could many things.

The relevant question here is: are they “certainly impending”? At least based on the evidence presented, the answer to that is “no.” And that is the legal standard that Plaintiffs must meet.

As the Supreme Court has held, this Court cannot “endorse standing theories that rest on speculation about the decisions of independent

actors.” See Clapper v. Amnesty Int’l USA, 568 U.S. 398, 414 (2013).Second, even if Plaintiffs had standing, their claims fail on the merits.

Plaintiffs essentially ask this Court to second-guess the judgment of the Pennsylvania General Assembly and election officials, who are experts in creating and implementing an election plan. Perhaps Plaintiffs are right that guards should be placed near drop boxes, signature-analysis experts should examine every mail-in ballot, poll watchers should be able to man any poll regardless of location, and other security improvements should be made.

But the job of an unelected federal judge isn’t to suggest election improvements, especially when those improvements contradict the reasoned judgment of democratically elected officials. See Andino v. Middleton,— S. Ct. —, 2020 WL 5887393, at *1 (Oct. 5, 2020)

Case 2:20-cv-00966-NR Document 574 Filed 10/10/20 =- (Kavanaugh, J. concurring) (state legislatures should not be subject to “second-guessing by an unelected federal judiciary,” which is “not accountable to the people”) (cleaned up).Put differently, “[f]ederal judges can have a lot of power—especially when issuing injunctions. And sometimes we may even have a good idea or two. But the Constitution sets out our sphere of decision-making, and that sphere does not extend to second-guessing and interfering with a State’s reasonable, nondiscriminatory election rules.” New Georgia Project v. Raffensperger, — F.3d —, 2020 WL 5877588, at *4 (11th Cir. Oct. 2, 2020).

As discussed below, the Court finds that the election regulations put in place by the General Assembly and implemented by Defendants do not significantly burden any right to vote. They are rational. They further important state interests. They align with the Commonwealth’s elaborate election-security measures. They do not run afoul of the United States Constitution. They will not otherwise be second-guessed by this Court.

I love that this young Federalist Society judge quotes Kavanaugh in supporting the principle (undercutting the Republican position in this case) that whatever the majority legislature decides to do regarding voting, unless it violates some specific constitutional or federal statutory provision, is legal.

fun fact from the decision:

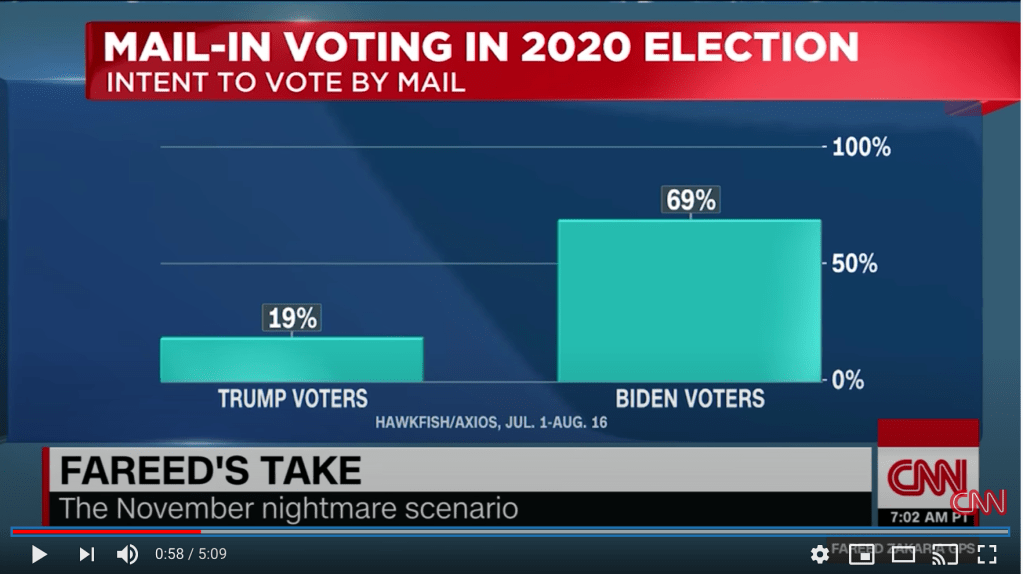

Indeed, Secretary Boockvar stated that as many as 16% of voters nationwide had cast their ballots using drop boxes in the 2016 general election, including the majority of voters in Colorado (75%) and Washington (56.9%).

Judge Ranjan on Summary Judgment (dismissal for failure to provide sufficient evidence to support a claim)

The summary-judgment stage “is essentially ‘put up or shut up’ time for the non-moving party,” which “must rebut the motion with facts in the record and cannot rest solely on assertions made in the pleadings, legal memoranda, or oral argument.” (citation omitted)

If the nonmoving party “fails to make a showing sufficient to establish the existence of an element essential to that party’s case, and on which that party will bear the burden at trial,” summary judgment is warranted (another citation– zapped)

A bit analyzing the anecdotal and expert testimony evidence presented by Team Trump (from page 61):

Based on the evidence presented by Plaintiffs, accepted as true, Plaintiffs have only proven the“possibility of future injury” based on a series of speculative events—which falls short of the requirement to establish a concrete injury. For example, Plaintiffs’ expert, Mr. Riddlemoser, opines that the use of “unstaffed or unmanned” drop boxes merely “increases the possibility for voter fraud (and vote destruction)[.]” [ECF 504-19, p. 20 (emphasis added)].

That’s because, according to him (and Plaintiffs’ other witnesses), theoretical bad actors might intentionally “target” a drop box as the “easiest opportunity for voter fraud” or with the malicious “intent to destroy as many votes … as possible.” (declaring that drop boxes “may serve as a target for bad actors that may wish to tamper with lawfully case ballots before such ballots are counted”).

But there’s no way of knowing whether these independent actors will ever surface, and if they do, whether they will act as Mr. Riddlemoser and Plaintiffs predict.

As to the rest of the “put up or shut up” evidence:

In addition to Plaintiffs’ expert report, Plaintiffs’ evidence consists of instances of voter fraud in the past, including an article in the N.Y. Post purporting to detail the strategies of an anonymous fraudster, as well as pointing to certain prior cases of voter fraud and election

irregularities (e.g., Philadelphia inadvertently allowing 40 people to vote twice in the 2020 primary election; some counties counting ballots that did not have a completed declaration in the 2020 primary election).Initially, with one exception noted directly below, none of this evidence is tied to individuals using drop boxes, submitting forged mail-in ballots, or being unable to poll watch in another county—

and thus it is unclear how this can serve as evidence of a concrete harm in the upcoming election as to the specific claims in this case.Perhaps the best evidence Plaintiffs present are the several photographs and video stills, which are depicted above, and which are of individuals who appear to be delivering more than one ballot to a drop box during the primary election. It is undisputed that during the primary election, some county boards believed it be appropriate to allow voters to deliver ballots on behalf of third parties. But this evidence of past injury is also speculative.

Initially, the evidence is scant. But even assuming the evidence were more substantial, it would still be speculative to find that third-party ballot delivery will also occur in the general election. It may; it may not.Indeed, it may be less likely to occur now that the Secretary issued

her September 28, 2020, guidance, which made clear to all

county boards that for the general election, third-party ballot delivery is prohibited. (“Third-person delivery of absentee or mail-in ballots is not permitted, and any ballots delivered by someone other than the voter are required to be set aside. The only exceptions are voters with a disability, who have designated in writing an agent to deliver their ballot for them.”). It may also be less likely to occur in light of the Secretary’s other guidance, which recommends that county boards place signs near drop boxes, warning voters that third-party delivery is prohibited.pp. 62-63

Naturally, for part of their failed denial of Equal Protection argument Trump/RNC lawyers cited Bush v. Gore. Judge Ranjan did find their argument persuasive, another of their arguments that failed “as a matter of law” :

In this respect, Plaintiffs argue that they suffer an equal-protection harm similar to that found by the Supreme Court in Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98 (2000). There, the Supreme Court held that the Florida Supreme Court violated equal protection when it “ratified” election recount procedures that allowed different counties to use “varying

standards to determine what was a legal vote.” Id. at 107.This meant that entirely equivalent votes might be counted in one county but discounted in another. See, e.g., id. (“Broward County used a more forgiving standard than Palm Beach County, and uncovered almost three times as many new votes, a result markedly disproportionate to the difference in population between the counties.”).

Given the absence of uniform, statewide rules or standards to

determine which votes counted, the Court concluded that the patchwork recount scheme failed to “satisfy the minimum requirement for nonarbitrary treatment of voters necessary to secure the fundamental right [to vote].”p.75

and

In addition to their equal-protection challenge to the use of drop boxes, Plaintiffs also appear to argue that the use of unmanned drop boxes violates substantive due process protected by the 14th Amendment. This argument is just a variation on their equal-protection argument—i.e., the uneven use of drop boxes will work a “patent and fundamental unfairness” in violation of substantive due process principles (substantive due process rights are violated “[i]f the election process itself reaches the point of patent and fundamental unfairness[.]” (cite removed). The analysis for this claim is the same as that for equal protection, and thus it fails for the same reasons. But beyond that, this claim demands even stricter proof. Such a claim exists in only the most extraordinary circumstances.

p. 92

Got to love that “plaintiffs also appear to argue…”

Judge Ranjan, analyzing the poll watcher issue, provides a nice example of the quality of the evidence presented by the Trump campaign and the Republican National Committee:

For example, in his declaration, James J. Fitzpatrick, the Pennsylvania Director for Election Day Operations for the Trump Campaign, stated only that the “Trump Campaign is concerned that due to the residency restriction, it will not have enough poll watchers in certain counties.”

Notably, however, Mr. Fitzpatrick, even when specifically asked during his deposition, never identified a single county where the Trump Campaign has actually tried and failed to recruit a poll watcher because of the county-residency requirement.

(“Q: Which counties does the Trump campaign or the RNC contend that they will not be able to obtain what you refer to as full coverage of poll watchers for the November 2020 election?

p. 124

A: I’m not sure. I couldn’t tell you a list.”).

and

Plaintiffs argue that the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic greatly reduces the number of people who would be willing to serve as a poll watcher, which further exacerbates the alleged problem caused by the county residency requirement.

The primary problem with this argument, though, is that Plaintiffs have not presented any evidence to support it. Plaintiffs have not put forward a statement from a single registered voter who says they are unwilling to serve as a poll watcher due to concerns about contracting COVID-19.

p. 128

[1]

Wikipedia gives the skinny on Judge Ranjan and his thoughtful handling of this shabby Trump/RNC attempt to suppress voting in a key swing state:

On July 10, 2019, his nomination was confirmed by a vote of 80–14.[9] He received judicial commission on July 12, 2019.

In August 2020, Ranjan ordered the Trump campaign to produce evidence of voter fraud in Pennsylvania by Friday, August 14. The Trump campaign must answer questions from Democratic groups, or admit to having no proof of election fraud. A hearing about the evidence is set for late September.[10] On August 23, 2020, Ranjan issued a stay on the Trump campaign’s lawsuit, pending the result of a similar state-level lawsuit.[11] On October 10, 2020, Ranjan denied the Trump campaign’s claims of voter fraud and allowed ballot dropboxes to remain in service.[12]