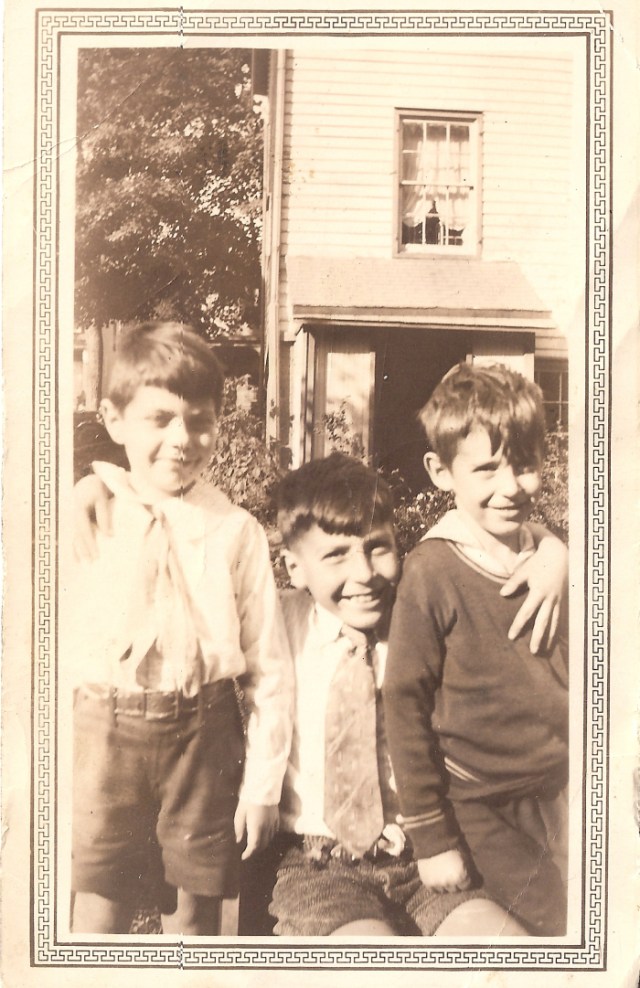

This photograph, taken at the nadir of the Depression, showed up in a box of photos we looked through after my father died. My father is in the middle, hand on the chest of his little brother Paul, the other arm draped around the shoulder of the urchin in the white shirt. They are all in short pants, and the two older boys wear ties, likely for school. I asked my uncle who the other boy was.

“That’s Herman,” my uncle said.

That was about all I learned. Herman was a friend who moved away from Peekskill not long after this picture was taken. I have no idea who took this picture, a person rich enough to own a camera, or if there was a particular reason it was taken on that sunny day. Maybe it was taken because Herman was moving and wanted a memento of his friends the Widem boys. I have no idea whose house that was behind them, it could well have been the house on Howard Street into which Uncle Aren put the impoverished family of his youngest sister.

I look at the photograph through a forensic lens, as an artifact of deep archeological interest. It is one of a small handful of photographic clues I can study. My father is clearly much bigger than his younger brother and Herman. He is sitting, or squatting, and almost the same height as they both are standing. I put my father’s age at seven or eight, based, in part, on my uncle looking five or six years-old. I’m thinking Herman must have been my uncle’s friend, though they all seem very cozy and friendly smiling for the camera.

The expressions and attitudes in photos, of course, can be grossly misleading. I think of a series of photos I found in an album of my mother’s, taken during a festive dinner at my parents’ house. I am beaming in every one of the photos on that two page spread. Grinning from ear to ear, my arm around my aunt, interacting with everyone with a huge smile on my face. The over-the-top happiness I am showing in every picture made me wonder what the hell I was so happy about. I did the math to figure out when the pictures were taken. Right in the middle of a six month period that felt to me like a profound depression, a time of personal darkness when I was monosyllabic and dreaded everything.

So I don’t put too much stock in the tender hand on my uncle’s chest, the smiles all around. My uncle flinched around my father right up until my father was on his death bed. It appears he had reason to flinch. The one story my father told, with some glee, from his unbearably awful childhood, was about the time he stuffed his brother’s mouth with raw chopped meat. Apparently well worth the ass-whupping he no doubt got for it, he chuckled about it decades later. So the tenderness for the camera, while charming, even endearing, doesn’t convince me very much.

Although, it must be said, when my father was dying, once I arrived in Florida, all he wanted to know is when his brother was getting there. I picked my uncle up at Ft. Lauderdale airport and from the time I brought him to the hospital the two Widem boys clung to each other. My sister and I were both struck by the poignance of that. After my father died, my uncle sat with his brother’s dead body, accompanied by my brother-in-law, until the hospital finally made arrangements for the body to be taken downstairs to be watched over by the Chevrai Kadisha, the Jewish burial society, eventually sent over by the Florida affiliate of the funeral home in New York.

What strikes me from the photo, outside of my father’s terrible haircut, the inexpert work of some family member, no doubt, is that my father, with his 20/400 vision, is still not wearing glasses. My father always wore glasses, he was legally blind without them. Late in his life a new laser procedure corrected his vision to virtually 20/20. For the first time in his life he didn’t need glasses to see beyond a foot or two, to drive.

“He looked so weird,” my mother told me, “that I made him get a pair of glasses with clear glass lenses and he wore those. I was so used to him with the glasses, he was almost unrecognizable without them.”

I remember the instant splitting head ache his glasses gave me the one time I tried to look through them. I have his last pair of glasses in my baritone ukulele case, where I put them when I took them off his face minutes before he died. The lenses are, indeed, clear glass.

But here’s my father, as a school kid, with no glasses. He’s looking at the camera, and the person instructing the boys to hold still and smile, and he’s seeing only a blur, benignly smiling at nothing he can see. How long would it be before the boy who grew up to become my father would get the glasses that saved him from life in the retarded class at that Peekskill elementary school?

There is nobody alive to answer most of the remaining questions I have. There are only the educated guesses of an amateur sleuth. And not a dispassionate sleuth, by any means.

I am understanding, slowly and by unsteady steps, that we don’t grasp anything important about deeply emotional things in a hurry. The pieces of the story we think we have start to come together in their own time, if enough focus is applied to them, if we are fortunate. The pieces that can never be known for certain become more or less likely after they are considered again and again, compared to other pieces that feel like they fit right.

I don’t pretend to understand how this process works, or even if it works, but it feels to me, some days, like the story of my vexing father is beginning to shape itself into a book.