I have reached the stage in trying to write a complete life of my father when I need the insights of other people who knew and loved him. It’s time to put on my journalist hat and reach out to them for corroborating details and information I don’t have any other way of getting. There is Phil Trombino, a younger colleague of my father’s from the Human Relations Unit (I don’t know how close they actually were, or how long they worked together, though I know my father liked him very much), there is his close friend of many years Benjy and a fellow in the East Bay named Rom who knew and very much dug my father’s routines when Irv was the director of Nassau-Suffolk Young Judaea and this guy was a teenaged member of the youth movement. I will attempt now to write a door for this man to walk through, into my telling of the story of Irv Widaen’s life, by way of introducing this narrative to him.

“You’ll send it to him, presumably, and then call, meaning many more weeks will probably pass before you actually get your head out of your ass and contact him,” said the skeleton of my father from his grave in Westchester County.

Yes, quite possibly.

“You still haven’t sent that postcard to that Trombino you found, about an hour from your apartment, to see if he is indeed the Phil Trombino who hit around .400 that year in college baseball at Iona, to find out, if he is, if he’d be willing to talk about his time at the long defunct Human Relations Unit.”

No.

“Needless to say, you haven’t reached out to Benjy since the night before mom died,” he added, needlessly.

Needless to say. Now back to this portal I am trying to construct today for Rom, who you knew as Bruce and later Peanuts, a guy I was always much closer to (I never recall even meeting Phil) that I also need to contact.

Nassau-Suffolk Young Judaea, like all the other Young Judaea regions around the country, held periodic conventions. A convention of as many kids as they could convene would be held at a camp or hotel and would take place over a weekend. Buses and cars would bring members of the youth movement together from clubs all over the region and an executive committee (the exec) would make a schedule of lectures, discussions, speakers, films, proposals, entertainments for the weekend. When my sister and I were little we attended a couple of these conventions at a hotel in a place called Hampton Bays. It was at one of these conventions that I first encountered the guy I am talking about, a young teenager called Bruce at that time.

Here is what I recall, from November 22, 1963, which must have been a Friday. We were driving out to Hampton Bays for the “convention”. My little sister and I had no idea what a convention was, we were about to see. My mother was in the passenger seat, most likely with the brilliant mutt Patches on her lap, and my sister and I were in the back. I was seven years old, though it’s hard for me to believe I could have been that young at the time. We stopped at a diner for lunch and the kid at the counter, who looked uncannily like a skinny version of JFK, thrust his face forward, a weird, pained smile on his face, and asked if we had heard. I guess everyone else in the place was in shock and we didn’t seem to be. The president had just been shot! The soda jerk was crying, as were many others in the diner.

My memory of that convention was mostly of sitting by the hotel office in the cavernous front hall, staring at a black and white television at the end of a long extension cord. I could not stop watching. I believe I was watching the live broadcast from Dallas on Sunday when they brought Lee Harvey Oswald out and a bull-backed Jack Ruby lunged forward and pumped a couple of pistol shots into Oswald’s abdomen, a moment captured in a famous still photo of Oswald’s sudden mortal agony. One of the cops holding Oswald’s arm recoils too, with an arresting expression of shock on his face too.

Ten years later I would be on a new kibbutz in the Aravah desert in Israel, volunteering to help pick their first bumper crop of tomatoes. It was common for kibbutz volunteers at that time to be assigned a family, a kibbutz mother and father to visit and hang out with. The kibbutz was brand new, and the members, most formerly American Young Judaeans, were only five or six years older than me. The kibbutz parents I was assigned were Ruthie, a kibbutznik on loan from another kibbutz, originally from Brazil, and a guy from Maryland, Howie Katz, a bright shining soul of infinite good cheer. Howie spent much of his time on the kibbutz naked, streaking from place to place, sometimes slipping on a pair of shorts.

The teenager I knew as Bruce, then Peanuts, now Rom, had served in the army with Howie, survived the explosion of their tank in Sinai, was also a member of the kibbutz. Rom was still on active duty somewhere, I think, I don’t recall seeing him on the kibbutz when I lived there.

Howie and I both returned to the US a few months later and we remained good friends for the rest of his life. Howie’s best friend, it turned out, was Rom, this fellow I am carving the portal for.

Rom corrected me, shortly after Howie’s sudden death in 2010, about Howie being my father though he was only three years older than me. He was actually five years older than me. Rom knew this because they were the same age and because his first image of me, Irv’s son, was at a convention in Hampton Bays when he was a in high school and I was a little kid, maybe in second or third grade. I am assuming that convention must have been in 1964, when I would have been eight and Rom, then still Bruce, would have been thirteen, probably the youngest Young Judaean at the convention.

Which would help explain why I noticed him by himself several times during that convention, outside the dining room, with his cane (hockey injury), imitating Eddie Giocamin as he narrated his game winning slap shot over and over, using the cane as a hockey stick. “Giacomin, slap shot, score!!!” he said as my sister and I laughed. (I discover now that Giacomin was a goalie, thus it is unlikely that my memory is correct, though I do remember him saying “slap shot, score!” and “Giocamin!!” several times as he slapped the imaginary puck toward the goal. Giacomin must have been saving all those attempted goals. I’ve never been a hockey fan.)

By 1964 the Beatles had landed in America and I was a big fan, especially of the irreverent John Lennon. This guy looked a bit like John, had the longish hair (as did I, in a child’s Beatle haircut), the wire frame glasses, the longish nose, the wry expression. He was also funny. Standing up shakily, using the cane as much as a prop as for support, he slurred “sure didn’t taste like tomato juice”, a reference to an ad for V-8 then common on TV about someone slipping the actor a spiked tomato juice. Well, you will say, that’s not what the ad was suggesting, it was about the superior taste of V-8, made with eight delicious vegetables. Still, I recall the line, recited in a drunken manner, and it made my sister and me laugh, as he took a couple of exaggeratedly drunken steps, glancing at us from the corner of his eye. Each time we passed him he would put on a little show for us. Whenever my father passed he’d say “get your ass back in the dining room, Bruce,” in passing, in that sly, breezily hassling way of his, not really seeming to care whether Bruce actually did it or not.

Years later I ran into him again as Howie’s best friend, in San Francisco. He’d been entrusted with filling Howie’s new waterbed, in the second floor walk up, and seeing how slowly it was filling, he took a stroll. When he came back he did his best to deal with the waterfall he’d accidentally caused. Howie laughed telling me the story. Rom is a great musician, keyboard and harmonica player extraordinaire, and I would get a chance to play a bit with him over the years. His dry sense of humor was intact, along with his humanism and sense of fair play. A very decent and likable fellow.

I called him when Howie died, to warn him that I’d inadvertently informed (through his mother) a former friend of Howie’s death. This guy was a famously difficult fellow who had angrily (and unfairly) written Howie off as a pussy-whipped wimp and was now headed to the funeral, and that I was so sorry. Rom reassured me that it would be fine and also recounted picking up Howie’s daughter at the airport, knowing he had to be the adult for her, and be strong, and then sobbing all the way back to Howie’s widow’s place by the Old Highway and the waves of the Pacific Ocean.

We had talked briefly after my father died, five years earlier. He told me my father was a great guy. I started to describe another side to the old man, the tremendous obstacles he labored long and hard to construct in the paths of his children, in this world of stumbling blocks, but Rom gently brushed it aside. He had nothing but fond memories of Irv, who was a great guy, and funny as hell. I was a great guy, too, for that matter, he pointed out. And that was the end of our discussion of Irv.

It would be interesting, and perhaps illuminating, to hear details from Rom, about his memories of the great guy who was my old man. How Irv looked from the point of view of a thirteen and fourteen year old kid who was not his own son. Their paths crossed a few years later at the camp my father directed, where Bruce, now Peanuts, was seriously injured in another accident. I can see that clearly too, how Irv must have looked to someone he simply affectionately shot the shit with, but details from Rom could add flavor to this telling.

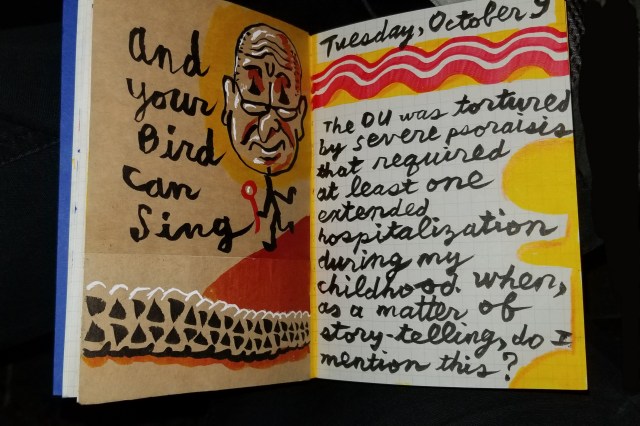

“Good enough, motherfucker, now send it off to him,” said the skeleton of my father, encouraged to see things moved forward 1/4 of an inch in the endless telling of his tale, before it’s too late.