When Friedman was a boy, (and his name was Mark, a name I should also use), his family spent some time, over the course of several summers, camping near Lake Sebago in bucolic Harriman State Park. Presumably they crossed the road by the family camping area and hiked up a trail to a beautiful manmade lake (you could see the blackened skeletons of the trees on the bottom in some places) that captured young Mark’s romantic heart. Some time around his thirtieth birthday Mark became determined to get into great shape. He began swimming regularly in a public pool near his apartment on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Then he remembered The Lake.

“Do you want to go to The Lake?” he’d ask. It was a beautiful spot, about an hour from the city, and the uphill hike was enough to get the blood pumping, up a tall hill on a rocky trail, down to a stream you cross on big rocks, up another hill, across a meadow, over a dirt road, and then, through the trees, a pristine, beautiful lake in a clearing. On a hot day, after an hour’s walk, there was nothing better than jumping into the cool, clear water of that lake. Mark used to drink the water as he swam from one end of the long lake to the other, back and forth. He would often swim for hours at a stretch, come out, eat something, have a couple of pulls on a joint, dive back in for a few more hours.

Here was the thing, though, after a refreshing dip, when you came out, there was little to do at The Lake. The rocky shores sloped toward the water, so you couldn’t stretch out anywhere without rolling downhill, or being on an awkward, uncomfortable angle on the rubble. You’d sit on a log. There were woods all around the lake and under the trees, after several hours, as the temperature began to go down, it often grew uncomfortably cool and clammy in the shade. Also, the swarm of ravenous mosquitos that hatched just before sunset, having little prey but Mark’s friend or two with him at The Lake, would joyously feast on anyone not in the water swimming.

After the first couple of trips to The Lake, unless you wanted to swim all day, there had to be a negotiation. Mark specialized in negotiations. He would offer to bring a joint, and chip in 60% so you could buy the provisions for the delicious speciality sandwiches that were eaten at The Lake, and he’d pay for gas (he drove his car up there) but you had to make the sandwiches, bring the drinks, and insect repellent, and anything to entertain yourself. There was always a negotiation with Mark, always.

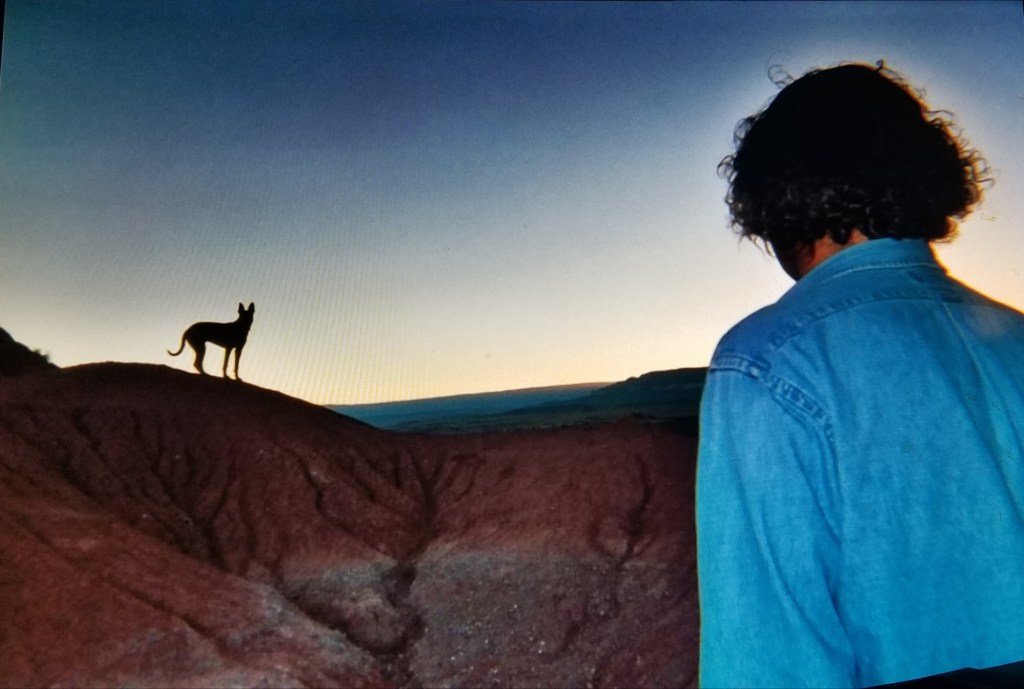

He named the lake Lake PeeDee, after his older brother’s Irish Setter, a dog he convinced his older brother to give him. (Years later I’d find Lake PeeDee a map, labeled Lake Wanoksink). PeeDee, who, in his doggish exuberance would run ahead on the trail, circle back, race ahead, circle back, would dive into The Lake as soon as we arrived, his orangey chestnut coat turning a dark burgundy as he got soaked. Like me, he’d pull himself out of the cool water after paddling around for a few minutes. Unlike me, he’d shake himself dry, curl up and fall into a deep sleep.

Sitting uncomfortably on the shore, or walking around in the itchy woods, fighting the mosquitos, and waiting for Mark to finish his interminable swim was as good a metaphor for our friendship as I can think of. It was a beautiful spot, no question, but it could also become a profoundly horrible spot if you were not swimming. The relative beauty or horror all depended on your perspective on how successful the negotiation had been. The measure of Mark’s art as a negotiator was that he always got what he needed out of the back and forth, that was the only way he knew to feel whole, I suppose, by winning. So unlimited swimming time was never on the table for discussion, his right to do that went without saying. That his winning always resulted in his later much greater loss never really dawned on him. This is why his life is a cautionary tale, boys and girls.

The tale is simple and brutally consistent in its outline. It is also the greatest example of the Repetition Compulsion that I know of. I think of it as a three act play. In act one he encounters a person or an idea that will magically transform his world. Swimming was one such idea, and it became an obsession. If a person, it was the one he’d been looking for his whole life: totally unlike anyone in his loser circle of depressed friends. This person was brilliant, funny, cool, wise, hip, strong, talented, nonchalant, deeply sensitive but not in a wimpish way at all. During Act One he’d wax rhapsodic and at length about this life-changing encounter with this amazing thing or person. It was literally going to change his entire world this time.

When the curtain went up on Act Two, things were beginning to become a little less than ideal. The idealized life-changer was showing signs of not living up to expectations. He didn’t actually feel that much better after swimming for hours at a time for a couple of years. The brilliant, funny, cool, wise person had a stubborn side, a petty side, was not always that funny– sometimes not funny at all– maybe wasn’t cool at all, and as for wisdom, not very wise, it seemed. There was a desperate element of dread hanging over Act Two as he realized he was about to be disappointed or betrayed again, which gnawed at him mercilessly as he reported these nagging suspicions.

The inevitable, brutal dramatic denouement of Act Three was only a matter of time, once Act Two was unfolding. When I think back, our friendship was a mutually exciting Act One then decades of Act Two, culminating in an extreme slow motion Act Three. Act Three was always the same, always bruising, always final and irrevocable. The other person was revealed as a supremely disappointing putz, ungrateful, unreasonable, disloyal, irrationally angry. Friedman’s demanding nature, and the constant nickel and diming of his eternal negotiations, of course, had nothing to do with this dramatic arc.

After seeing the identical play many times over the years, I’d become impatient when he’d insist on describing acts two and three in great detail. Nobody listened to him, that was one of his fondest laments, and so, as his oldest friend, the least I could do was fucking listen to him and let him tell his own story. Yet, human nature being what it is, I became less and less able to keep myself from making premature, if accurate, predictions each time he told the latest iteration of his eternal story.

“OK,” I’d say, having grasped by his telling that Act Three had already transpired, “so did he rip you off, physically attack you, curse you out, slander your name, steal from your business, smash your windshield or sack your home?” This kind of question would drive him wild– who was telling the story, him or me?! He would glare, arms crossed over his chest, the picture of active churlishness. I realize now how painful it must have been to him, being constantly betrayed by vicious putzes and his oldest friend acting like a dickishly superior theatre critic, breaking in to critique a play directed by his lab rat, a play he once again hadn’t even sat through til the end.

Finally, after every detail was recounted, he’d reveal the dramatic ending: he confronted me in a rage when I chanced on him at a restaurant, loudly called me a fucking Jew, threatened to punch my face in, never paid me back the money I loaned him, or even answered my calls or emails.

OK, I’d think, better than the time he was punched in the face, called a fucking Jew, and they later broke into his business and loaded up a truck with his provisions. Better than the time they ransacked his house and stole his bicycle. Better than that wedding for one of his workers, the one he’d been flattered to be invited to, until he noticed that all the food had been stolen from his own commercial kitchen. Better than the lawsuits. If I made any of these comments he’d snarl, I was missing the point — his life was cursed, he was doomed to a parade of fucking betraying putzes! Including, it went without saying, me.

Of course, the question in your mind at this point must be, how on earth could you have been friends with someone this clueless and toxic for so many years? What possessed you to continue going up to The Lake to be miserable? Good questions, and I will begin to provide the answers that I have, when this tale continues.